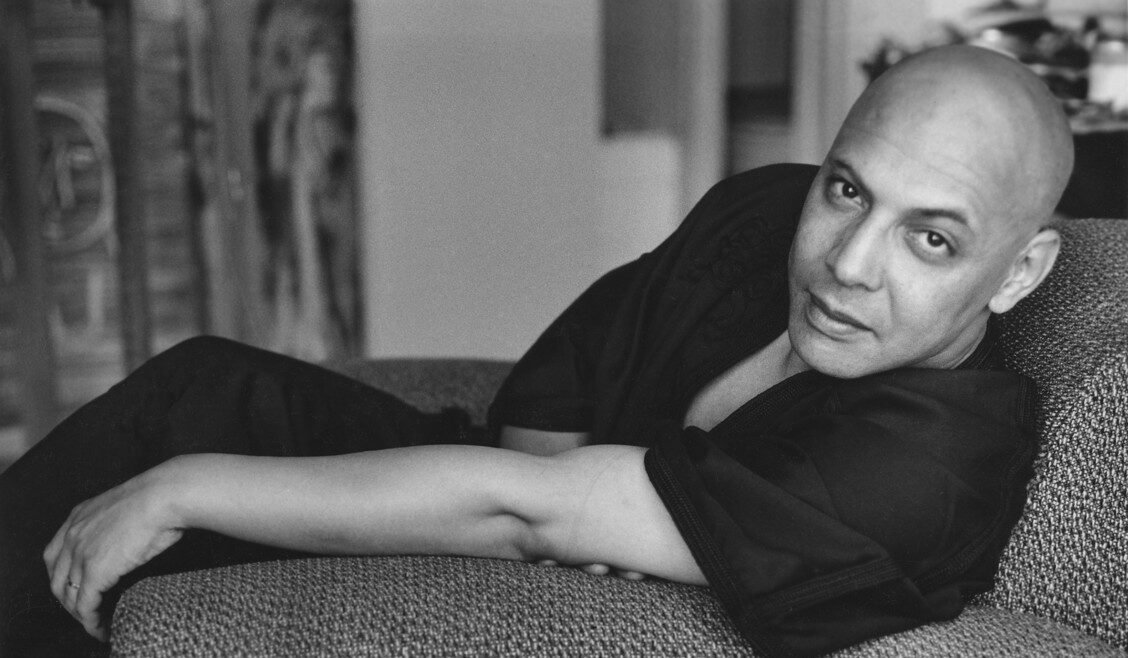

Across the landscape of modern Arab and North African art, few figures embody the tension between tradition and modernity as vividly as Ahmed Cherkaoui. Though his life was brief, his artistic legacy remains deeply resonant, especially for audiences in the Middle East who continue to navigate the balance between inherited cultural identity and contemporary global expression. Cherkaoui’s work speaks to this shared regional experience: a visual language that draws from ancestral memory while engaging the modern world with urgency and experimentation.

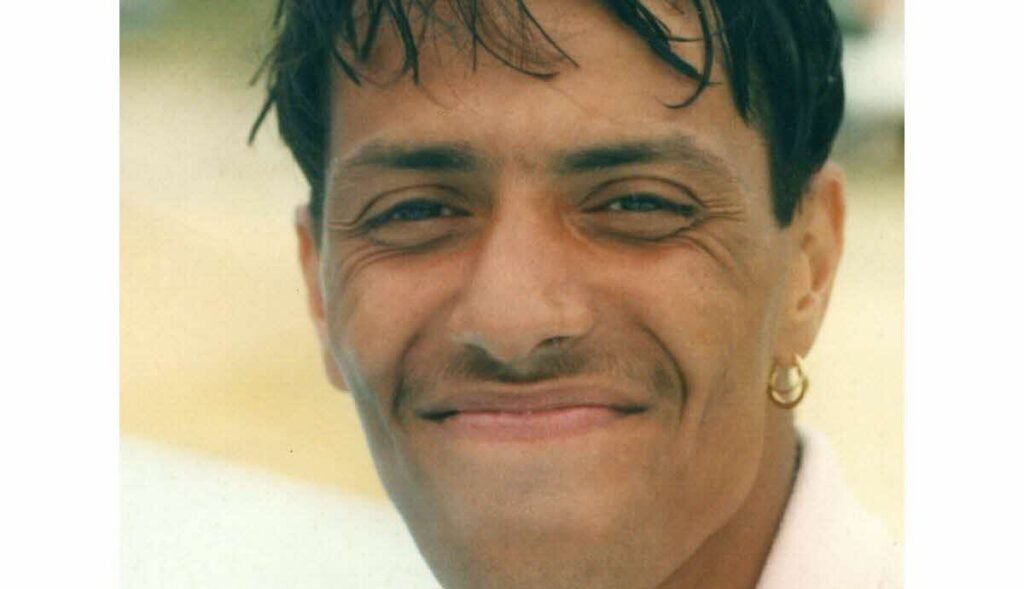

Born in 1934 in Boujad, Morocco, Cherkaoui grew up in an environment steeped in craft, spirituality, and symbolism. His mother was a weaver, and the rhythms of textiles, embroidery, and decorative motifs formed part of his earliest visual vocabulary. Long before he encountered European modernism, he was absorbing a living tradition of patterns and signs, symbols that would later resurface in his paintings as a distinctive and unmistakable artistic signature.

From Boujad to Paris: A journey of discovery

Cherkaoui’s artistic path led him to Paris in the 1950s, a time when the city remained a global epicenter of modern art. Like many artists from the Arab world and North Africa during the mid-20th century, Paris represented both opportunity and challenge. It offered access to artistic movements, galleries, and intellectual networks, but also confronted artists with the pressure to define themselves within a Western art historical narrative.

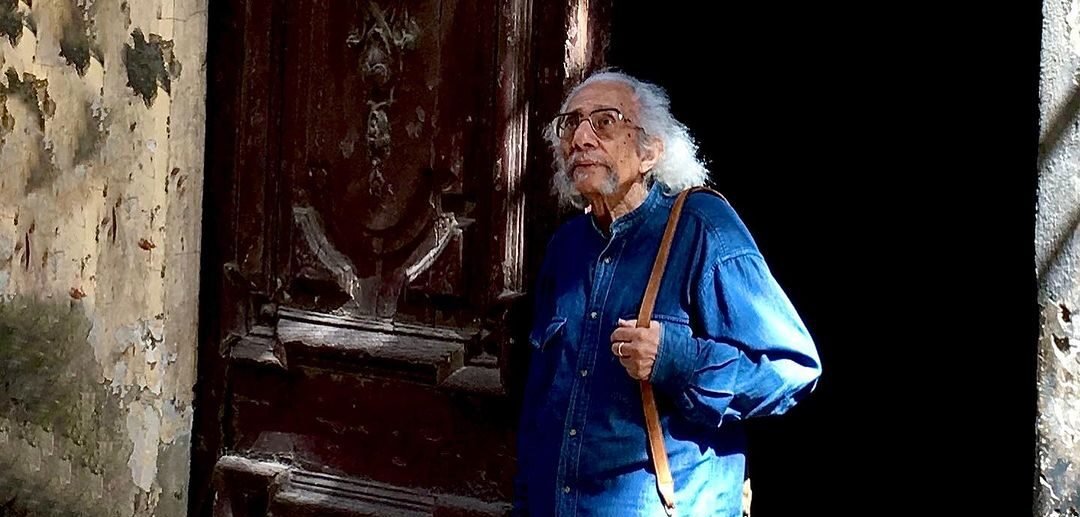

Rather than imitate European styles, Cherkaoui used his time in France to sharpen his artistic language. He studied at the École des Métiers d’Art and later at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. There, he encountered abstraction, expressionism, and the evolving avant-garde. Yet instead of abandoning his roots, he began a process of rediscovery. He traveled across Morocco to document Amazigh tattoos, carpets, pottery, and rural visual traditions. These journeys became foundational to his practice, allowing him to reclaim indigenous symbols as contemporary artistic tools.

This act of cultural retrieval carries particular resonance for Middle Eastern readers. It echoes broader regional conversations about identity, postcolonial self-definition, and the need to reinterpret heritage through a modern lens.

The language of symbols and signs

Cherkaoui’s paintings are instantly recognizable for their dense constellation of symbols. These marks, abstract yet deeply rooted, draw from Amazigh iconography, talismans, and spiritual motifs. Rather than presenting these elements as ethnographic references, Cherkaoui transformed them into an expressive visual language.

His canvases often feel like living surfaces. Symbols float, overlap, and interact in rhythmic compositions that evoke textiles, calligraphy, and ritual objects simultaneously. The result is a form of abstraction that feels intimate and cultural rather than detached or purely formal.

For audiences across the Arab world, this approach resonates strongly. The region’s artistic traditions, from Islamic geometry to calligraphy and textile design, have long privileged pattern, repetition, and symbolic meaning. Cherkaoui’s work demonstrates how these visual traditions can evolve without losing their essence.

In his paintings, symbols become emotional carriers. They communicate memory, spirituality, and identity without relying on literal representation. The viewer is invited to feel rather than decode, a quality that aligns closely with the poetic and metaphorical traditions of Middle Eastern storytelling.

A pioneer of Moroccan modernism

Cherkaoui is often described as one of the founders of Moroccan modern art, and the title is well deserved. During the years following Moroccan independence in 1956, the country’s cultural scene was transforming. Artists sought to break away from colonial frameworks and build a national artistic identity that could stand confidently on the global stage.

Cherkaoui played a pivotal role in this shift. His work challenged the assumption that modern art must follow Western trajectories. Instead, he demonstrated that modernism could emerge organically from local heritage.

This idea, modernity without cultural erasure, remains a powerful theme across the Middle East today. From architecture to music to design, creatives throughout the region continue to grapple with similar questions: How do we move forward without losing ourselves? How do we innovate without forgetting where we come from?

Cherkaoui’s career offers one possible answer: by turning heritage into a living resource rather than a nostalgic relic.

Spirituality and the unseen

A spiritual dimension runs through much of Cherkaoui’s work. His symbols often evoke talismans, protective signs, and ritual markings. There is a sense that his paintings operate in a space between the visible and the invisible.

This spiritual undertone connects deeply with cultural sensibilities across the Arab world, where art has historically been intertwined with spirituality and metaphysical reflection. Cherkaoui’s canvases feel contemplative, almost meditative. They invite viewers to pause, reflect, and engage with the unseen layers of meaning beneath the surface.

Rather than depicting religious imagery directly, he evokes spirituality through atmosphere and symbolism. The effect is subtle yet powerful, an art that feels sacred without being literal.

A life cut short, a legacy that endures

Tragically, Ahmed Cherkaoui’s life was cut short in 1967 when he passed away at the age of just 33. Yet in less than a decade of active work, he produced a body of art that continues to influence generations of artists across North Africa and the Middle East.

His early death lends his career a sense of urgency. Looking at his paintings, one feels the intensity of an artist racing against time, determined to articulate a new visual language for his culture. The brevity of his life also raises an intriguing question: what might he have achieved had he lived longer?

Despite this loss, his impact continues to ripple outward. Today, Cherkaoui’s work is exhibited internationally and remains a cornerstone of discussions about modern Arab and African art. His paintings continue to inspire artists exploring identity, abstraction, and cultural memory.

Why Cherkaoui matters today

For contemporary audiences in the Middle East, Ahmed Cherkaoui’s story feels remarkably current. The questions he explored, identity, heritage, global dialogue, and cultural authenticity, are still at the heart of artistic practice in the region.

In an era shaped by globalization, migration, and digital connectivity, many artists find themselves navigating multiple cultural worlds simultaneously. Cherkaoui’s work offers reassurance that hybridity can be a source of strength rather than conflict.

He reminds us that modernity does not require abandoning tradition. Instead, tradition can be a foundation for innovation, a wellspring of symbols and stories waiting to be reimagined.

A bridge between worlds

Ultimately, Ahmed Cherkaoui’s legacy lies in his ability to build bridges: between past and present, between Morocco and the world, and between tradition and modernity. His art stands as a testament to the richness of cultural dialogue and the power of visual language to transcend borders.

Ahmed Cherkaoui may have lived only three decades, but his art continues to speak across generations. In the evolving narrative of modern Arab and North African art, his voice remains clear, vibrant, and profoundly relevant.